- Introduction

- 大掃除 ”o o so u ji ” – Year-End Deep Cleaning

- 仕事納め ”shi go to o sa me ” – The Last Working Day of the Year

- Spending Time at My Parents’ Home

- New Year Decorations – “shi me na wa ”, “ka do ma tsu ”, and More

- 餅つき ”mo chi tsu ki” – Making Rice Cakes

- “Ka ga mi Mo chi ”– An Offering to the Gods

- “o o mi so ka” – New Year’s Eve

- 年越し蕎麦 と 除夜の鐘 ”to shi ko shi so ba” and “jo ya no ka ne”

- New Year’s Greetings and “ha tsu hi no de”

- “o to shi da ma” – New Year’s Money for Children

- “o se chi” and “o zo u ni ” – New Year’s Food

- “ka gu ra” – Traditional Sacred Dance

- “ha tsu mo u de” – First Shrine Visit of the Year

- Closing Thoughts

Introduction

Hello everyone.

How are you spending the end of the year?

My name is Miyabi. I am Japanese and I live in Japan.

Today, I’d like to introduce how I spend the year-end and New Year holidays.

This article is especially for foreigners who are experiencing a Japanese-style New Year for the first time through international marriage, and for anyone who is curious about how Japanese people typically spend this season. I hope this will be helpful for you.

Many Japanese people travel abroad during the New Year holidays, but I personally spend a very traditional Japanese “o sho u ga tsu” every year. You could say I’m a person from the “good old days” of Japan.

This time of year is when I strongly feel my connection to relatives, so the year-end and New Year holidays are a very special time for me.

大掃除 ”o o so u ji ” – Year-End Deep Cleaning

As the end of the year approaches, we begin “o o so u ji ” (year-end deep cleaning).

Because we want to welcome the New Year feeling refreshed, we clean thoroughly and remove all the dirt that accumulated over the year.

We clean things like window screens, the kitchen ventilation fan, air conditioner filters, and bathroom drains until everything is spotless.

My grandmother used to say that we clean in order to welcome the “to shi ga mi sa ma ” (the New Year deity)年神様.

仕事納め ”shi go to o sa me ” – The Last Working Day of the Year

December 28 is often designated as “shi go to o sa me ”(the last working day of the year) by many companies.

When leaving work on that day, people say, “yo i o to shi o!”「良いお年を!」

This phrase means, “Please have a good New Year.”

When speaking to a superior, we say it more politely:

“yo i o to shi o o mu ka e ku da sa i.”「良いお年をお迎えください」

Although it depends on the industry, many companies do not see their coworkers again until January 4.

Spending Time at My Parents’ Home

From around December 29, I spend every year at my parents’ home.(My husband’s parents are deceased.)

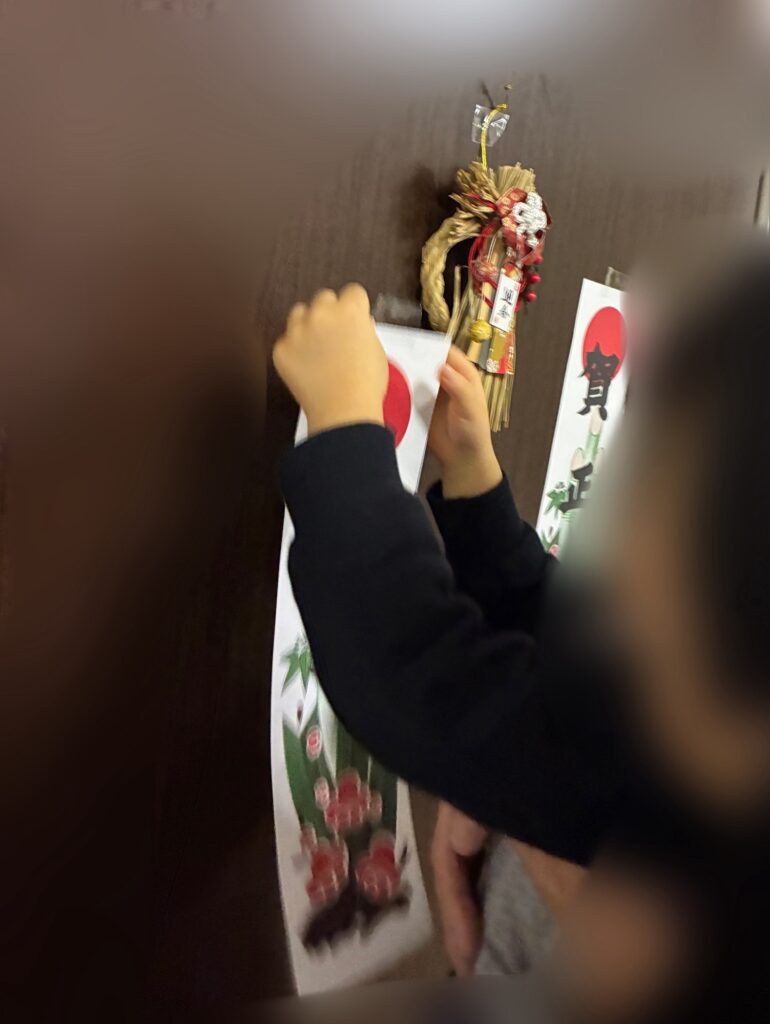

New Year Decorations – “shi me na wa ”, “ka do ma tsu ”, and More

Around December 30, we decorate the house for the New Year.

We put up paper with the celebratory words “ga sho u” written on it on the door, and we hang “shi me na wa”.

“shi me na wa” is said to act as a spiritual boundary that prevents evil spirits from entering the home.

In the past, some people even decorated bicycles and cars with shimenawa, but this is rarely seen nowadays. Times have changed, and fewer households decorate with shimenawa at all.

Some families display bamboo decorations called “ka do ma tsu”. These are quite expensive, so my family has never displayed them. However, you often see kadomatsu at department store entrances during the New Year season.

餅つき ”mo chi tsu ki” – Making Rice Cakes

Also around December 30, we do “mo chi tsu ki” (rice cake making).

Every year, my relatives and I gather at my grandmother’s house to make mochi.

In the past, steamed glutinous rice was placed in a large wooden mortar called an “u su ” and pounded with a large hammer-like mallet called a “ki ne”.

However, it’s very hard work and hurts your lower back, so these days we use a mochitsuki-ki (a rice cake machine).

It’s an electric machine that automatically pounds the rice into mochi.

Once the mochi is ready, we divide it into small pieces, shape them, and let them dry. Drying allows the mochi to last longer, making long-term storage possible.When it’s time to eat, the mochi becomes soft again if you grill it or boil it in water or soup.

I always look forward to mochitsuki day because we can eat freshly made mochi.

Mochi is delicious with sweet red beans (anko), or with kinako (soybean flour) and sugar.

There are also many savory ways to eat it: with grated daikon radish (daikon oroshi) and ponzu, with natto, with soy sauce, or added to soups like miso soup.

Mochi is actually eaten in many different ways in Japanese households.

“Ka ga mi Mo chi ”– An Offering to the Gods

One of the dried mochi is displayed in the room as an offering to the gods. This offering is called kagami mochi.

Every year, my grandmother makes kagami mochi using the mochi we made together.

However, since fewer families make mochi at home nowadays, store-bought kagami mochi is also widely available.

“o o mi so ka” – New Year’s Eve

December 31 is called “o o mi so ka ” (New Year’s Eve).

I spend this day at my parents’ home every year. This year, my grandmother also stayed over, so we spent the day together with my husband, our children, my parents, and my grandmother.(My husband’s parents are deceased.)

For dinner, we often eat “na be” (hot pot), sharing one pot together. This year, we had “su ki ya ki”.

年越し蕎麦 と 除夜の鐘 ”to shi ko shi so ba” and “jo ya no ka ne”

Around 11:30 p.m., we eat toshikoshi soba (year-crossing soba).

Since we already had dinner, I usually eat only about half a serving.

We eat soba because noodles are long, symbolizing a wish for a long and healthy life.

Also, soba noodles are easier to cut than udon, which represents cutting off bad relationships and misfortune.

As midnight approaches, bells called joya no kane are rung at Buddhist temples, and their sound echoes throughout the town.

The bell is rung 108 times, which is said to represent the number of human desires (bo n no u).

Hearing the bell every year makes me truly feel that the year is changing. The deep, resonant sound is very moving.

When the year changes, everyone says, “a ke ma shi te o me de to u” あけまして おめでとう

New Year’s Greetings and “ha tsu hi no de”

On the morning of January 1 (Gantan), when we wake up and see each other, we greet one another by saying:

“ a ke ma shi te o me de to u go za i ma su. ko to shi mo yo ro shi ku o ne ga i shi ma su.”「あけまして おめでとうございます。今年もよろしくお願いします。」

This greeting celebrates the New Year and humbly expresses a wish to maintain good relationships throughout the year.

My grandmother bows very formally and politely every year, which always makes me feel a little shy.

Then, we watch the first sunrise of the year (ha tsu hi no de) and pray with our hands together.

“o to shi da ma” – New Year’s Money for Children

During the New Year, children receive otoshidama (New Year’s money) from adult relatives.

The money is exchanged at a bank for brand-new bills that have never been used, and then placed into decorative envelopes called pochi-bukuro.

I looked forward to this very much when I was a child. Now, I’m on the giving side instead.

“o se chi” and “o zo u ni ” – New Year’s Food

On New Year’s Day, we eat osechi, a special bento-like New Year meal.

It is said that on “ga n ta n”(On New Year’s Day), people should avoid housework and cooking as much as possible, so osechi is prepared in advance for this purpose.

Families who make it by hand prepare it from December 31.

My family used to make it every year, but this year we bought it.

The dishes in osechi are chosen because they last a long time, and each ingredient has an auspicious meaning.

For example, shrimp symbolize longevity because their shape resembles an elderly person with a bent back.

There are many more meanings, but they are difficult to understand unless you are an advanced Japanese learner, so I’ll skip them this time.

Although we try to avoid cooking, it’s cold, and we still want soup, so we always make “o zo u ni”.

“o zo u ni” is a soup with mochi. Some families use miso, while others use clear dashi broth.

“ka gu ra” – Traditional Sacred Dance

This year, we were able to watch kagura at a shopping mall on New Year’s Day.

Kagura is written as “神楽,” meaning “to entertain the gods.”

It originally began as a ritual dance to please the gods, and while that aspect remains, it has also developed as entertainment for ordinary people.

Iwami kagura from Shimane Prefecture is especially famous.

It is based on Japanese mythology and often depicts scenes of defeating demons (oni).

The performance I saw was called Rashōmon. In this story, a hero cuts off the arm of a demon, but the demon disguises itself as an old man to retrieve it.

The role of the demon is played by the most skilled dancer. When portraying the old man, the dancer makes their body appear small, and when becoming the demon, they make their body appear large.

The movements are completely different, and kagura is truly fascinating.

If you search “Iwami Kagura” 「石見神楽」on YouTube, you can see what it’s like.

The performance “Yamata no Orochi” is also amazing.

There is very little dialogue, so even if you don’t understand Japanese, you can enjoy it!

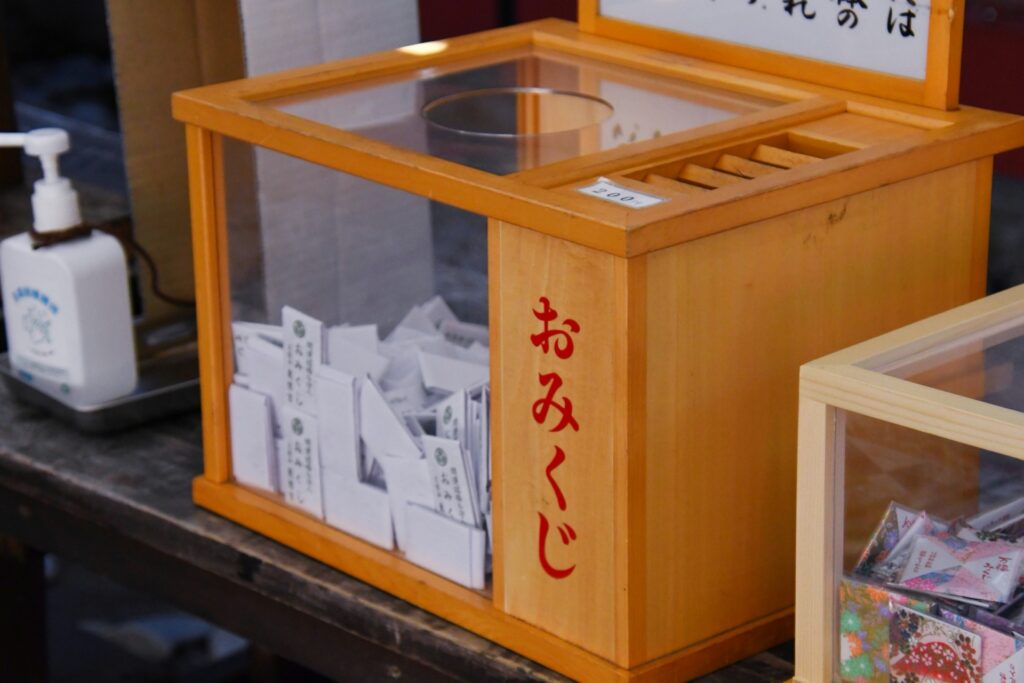

“ha tsu mo u de” – First Shrine Visit of the Year

Around January 1 or 2, we go to hatsumōde.

Hatsumōde means visiting a shrine or temple for the first time in the New Year.

It feels like going to show our faces to the gods at the start of the year.

Japan is said to have over eight million gods (yaoyorozu no kami), so I’m honestly not sure which god I’m visiting each year, but I always go to the shrine closest to my home.

In Japan, there is a concept of tochi-gami-sama (local guardian deities), meaning each area has its own god.

So I go to greet the god nearest to my house.

At the shrine, I buy a hamaya every year. Hamaya is a sacred arrow used to ward off evil.

There are many other items too, such as charms for household safety or business success.

Many people pray with wishes like “Please let me pass my exams” or “Please let me become rich.”

However, I don’t make such a wishes.

Every year, I pray like this in my heart:

“Thank you for always watching over us. I will do my best with what I can handle on my own. For the things beyond my reach, please lend me just a little strength. Please watch over us, and may everyone stay healthy and safe throughout the year.”

I feel that if gods exist, they can’t possibly listen to everyone’s wishes.

So perhaps asking for things is a mistake, and gratitude is what we should offer instead.

Still, there are moments in life when fate alone determines life or death, so I can’t help but hope for a little good fortune during those times.

When I say “please protect us,” I’m actually more often thinking of my ancestors.

Since they are connected to me by blood, I feel they might favor me a little.

Japan is not very religious in a strict sense, so views on life and death vary widely, and many values are mixed together.

For example, I attended a kindergarten affiliated with “jo u do shi n shu u ” Buddhism, middle school through university at Christian schools, and now I belong to ”so u to u” Zen because of my husband’s family.

From a foreign perspective, that probably sounds very confusing.

Japanese people often belong to religions mainly for funeral purposes, but their way of thinking is quite close to being non-religious.

Many people pick and choose the parts they like from various religions.

Interesting, isn’t it?

Omikuji: Fortune-telling paper at Japanese shrines

Closing Thoughts

And that’s the end of my story about the year-end and New Year.

How do you spend this time in your country?

By learning about each other, I truly believe the world can become more peaceful.

I’m very grateful for the development of the internet.

That’s all from Miyabi!

I write articles about Japan, teach Japanese through writing, and run a Japanese-learning YouTube channel called Japan Phrase Adventure.

Thank you very much, and I hope to continue connecting with you in the future.